If you open a New Testament textbook, even one purporting to approach the topic from a historical perspective, you will no doubt encounter numerous intriguing—and often very specialized—categories and classifications. This specialized terminology might include some or all of the following: fulfillment citation, Gnostic Christianity, infancy gospel, Pauline Christianity, kerygma, Synoptic Gospel, Transfiguration, Johannine traditions, messianic secret, criteria of authenticity, inter alia. Some of these terms, like fulfillment citation and messianic secret, are not used by our ancient sources themselves; instead, they are categories that scholars have invented and decided to employ to help make sense of distinct features in early Christian writings. Others, such as kerygma (the transliteration of the ancient Greek term for “proclamation,” κήρυγμα), are used in early Christian texts,[1] and indeed, kerygma has come to be used by New Testament scholars as a special shorthand for the basic message about Jesus and the salvation he offered—thus, for instance, the so-called Pauline kerygma (encapsulated well in such passages as 1 Thessalonians 1:9-10 and Romans 1:3-4). Yet curiously, other historians of the ancient Mediterranean world would likely not use the term kerygma when discussing the ideas of salvation associated with Greek or Roman deities. Why, they might then wonder, does Christianity get a specialized term for “message of salvation” when numerous other non-Christian groups in the Roman Empire also promoted messages of salvation and aren’t bequeathed unique terminology by scholars? Similarly, why do New Testament scholars use the special category of “infancy gospel” to classify stories about Jesus in his youth? Why don’t we have a similar special category of literature for the Greco-Roman stories that concern divine figures in their early years as well?

It is a peculiar state of affairs. Scholars who study the origins of Christianity, I might even venture to suggest, are rather obsessed with such categories and terminology—perhaps more so than our counterparts in other areas of ancient history. The use of so many unique categories offers us excellent opportunities to reflect on how these categories operate in our analyses of the past. In what follows, I will think more about how we make these categories “work” for us and why it’s necessary to reflect on them and their effect on our data.

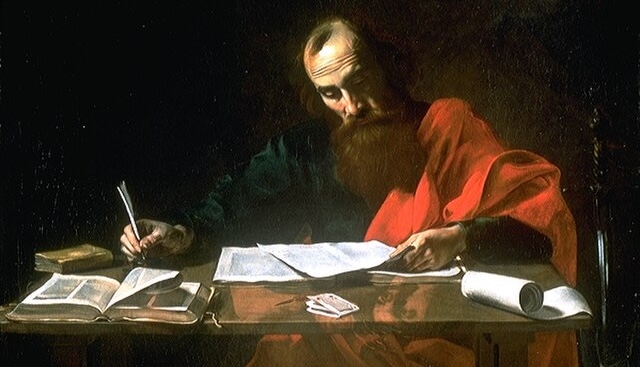

Let us consider an example at length: the seemingly straightforward classification of “Pauline Christianity.” According to one definition, Pauline Christianity is “the theology and form of Christianity which developed from the beliefs and doctrines espoused by the Hellenistic-Jewish Apostle Paul through his writings and those New Testament writings traditionally attributed to him. Paul’s beliefs were rooted in the earliest Jewish Christianity, but they deviated from this Jewish Christianity in their emphasis on inclusion of the Gentiles into God’s New Covenant and in his rejection of circumcision as an unnecessary token of upholding the Mosaic Law.”[2] In laypeople’s terms, Pauline Christianity is the form of Christianity attested in the 13 letters attributed to Paul in the New Testament. Simple enough.

The categorization of “Pauline Christianity” has done some important work for scholars, especially in helping us see literary relationships among texts and identify ideological similarities and differences. To be sure, it does help us group together a range of letters in the New Testament that illustrate a certain openness to non-Jews. And if we take letters such as Galatians as evidence, there were clearly other ancient people who did not embrace Paul’s ideas about non-Jews having access to the salvation offered by the Jewish deity, so it makes sense to categorize together texts that appear to agree on this matter.

But this classification invites some problems if used without careful theoretical reflection. First of all, we must recognize that the category of “Pauline Christianity” is deduced from letters that promote a certain ideal for following Jesus. In other words, the category is built on discursive evidence. We have no way of knowing the extent to which the people on the other side of Paul’s letters actually expressed the ideals he espoused. In fact, the very fact that he regularly corrects the theology and practices of his audiences in letters such as Galatians and 1 Corinthians suggests that the “Pauline Christianity” that scholars have reconstructed from his letters might not have even existed in the way Paul describes. It is possible, moreover, that he is bringing their whole group existence into being solely in the space of his letters. First Corinthians 1, for instance, attests to different factions among his Corinthian audience—could this mean that the Corinthians don’t even see themselves as part of the same Christ group? Or further: that their unified “community” only exists in Paul’s mind and in his letters to them?

The fact that such an abstract form as “Pauline Christianity” is based in large measure on textual evidence invites other concerns, too, about the nature of the evidence upon which we based historical reconstruction. To be sure, this is a perennial problem for ancient history; we are limited by those few written sources and items of material culture that survive—and these reveal only a narrow portion of the human experience in antiquity that we are studying. And to complicate matters more: as we all recognize, people can write about things that do not exist—or that do not exist how they want them to exist. To what extent is this the case (if at all) with Paul’s letters, and with the phenomenon of “Pauline Christianity”?

Further, the category “Pauline Christianity” imposes, to some extent, a rigid form of Christianity on whatever was really going on among Paul’s addressees. As scholars regularly caution, the distinctive nomenclature of “Christian” did not emerge until the late first century, decades after Paul and the canonical gospels were written. Paul himself uses a range of phrases to talk about people expressing fidelity to Christ, but never “Christian.” Perhaps the explanation is simple: the word did not yet exist in his time. But it is also possible (likely, in my view) that Paul still viewed his entire enterprise in terms of Judaism and that he saw himself as widening the access points, so to speak, into the salvation offered by the Jewish god.

If we use “Pauline Christianity” to describe these groups, then, we’re forcing them to accord with terminology that 1) was created by scholars on the basis of sparse, ambiguous textual references, and that 2) imposes an identity on them that, for whatever reason, they themselves were not using. These two points suggest that this seemingly innocuous terminology could significantly distort our data, convincing us that certain coherent and identifiable groups of “Pauline Christians” existed behind Paul’s letters. But if we could take a time-machine back to, say, ancient Corinth (which would indeed solve so many problems!), we might discover that nowhere in the city could we find people who matched the idealized “Pauline Christians” that exist in our imaginations and in our New Testament textbooks.

Given these issues I have raised about this terminology, one might right ask, “Well, did Pauline Christianity exist or not?” Or, “is it just a scholarly construct?” In a way, yes, it is a construction of scholars, but almost all academic abstractions are invented. Scholars invented the nomenclature of “the Dark Ages” and “the Agricultural Revolution” too—in the sense that no one living in those times used those categories in their native discourse. The difference between native terminology and scholarly categories has been extensively discussed among scholars, but acknowledging the constructedness of a category is fairly low-hanging fruit. Realizing the constructedness of terminology should be our starting point, and the subsequent question must be: what are we going to do from there? In all cases, we must go further, as I have done here, and ask: What are the consequences of such categorization? What does it help us see? What does it occlude? In other words, what effect is it having on our data?

Just as important, we should ask: why are we compelled to categorize? Scholars who study the history of Christianity, as I suggested above, seem to invent categories more often than other historically-minded scholars, perhaps in an effort to standardize and/or systematize the origins of Christianity and render it a clear, systematic movement that unfolded in an intelligible trajectory. Categories and classification help make that possible. But there is a dark side too: the categories we make literally determine the future—at least in the sense that they influence what we then go on to recognize as legitimate knowledge and future research. For this reason, it is crucial to understand how they work. To be clear, I am not suggesting we abandon the nomenclature of Pauline Christianity or any other scholarly category. But we have to understand how they package the ancient evidence, perhaps sometimes distorting it or even disguising it, so that it looks “familiar” to us and more amenable to the knowledge frameworks we currently operate with. With respect to the case study here, we cannot treat Pauline Christianity as somehow a perfect reflection of a religious reality that existed in the first century. To be blunt, it is far more complicated than that. Recognizing that complexity and reflecting on its consequences should be a routine part of our work in studying early Christianity.

[1] As in Luke 11:32, “the proclamation of Jonah.” It is more frequently found in the cognate form of κηρύσσω (lit. “I proclaim”). Just as with the term “gospel,” this ancient Greek word is found in non-Christian literature, at least initially, but (also like “gospel”), its meaning becomes totally dominated by its Christian usage. Thus, the Wikipedia entry is solely dedicated to its Christian usage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerygma

[2] While this basic definition is drawn from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_Christianity), there are countless textbooks and scholarly monographs that adopt such nomenclature as well.

Leave a reply to Jerry Cancel reply