It was in my third year of graduate school that I took prose composition for Latin and Greek and was tasked with finding a text to translate into each of these languages. The professor’s recommendation was to pick Thucydides to translate into Latin prose, probably in an attempt to pacify Longinus’ manes in whatever manuscript library or rhetoric classroom it had taken residence. Since I was also taking the graduate Sanskrit translation seminar along with my Greek and Latin coursework, I decided I’d pick a classical Sanskrit work from ancient India to translate into each of the Mediterranean Classical languages. For those of you who might not know, Sanskrit is the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) derived ancient Indian language originally used for liturgical hymns, but later on for most high-status literary works upon which earlier scholars placed the label “classical” though exactly what that means outside the Mediterranean is something that Phiroze Vasunia has written about extensively.[1] But I digress. With an interest in ekphrasis and philosophical dialectic, I decided to pick passages from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (8th cent. BCE) and the Bhagavad Gīta (~5th cent. BCE) to translate into Greek and Latin, respectively. While I’ll discuss the latter here, both projects are relevant to my discussion.

My reasons for undertaking this type of translation project were numerous. First, since my dissertation project centered around the ~2nd century CE Sanskrit astrological manual titled the Yavana Jātaka (transl. “The Greek Horoscopy”) which scholars past had claimed was translated from Greek into Sanskrit in ancient Alexandria, I wanted to see if that was actually possible, or at least how one would go about doing something like that.[2] While I recognized that translating sacred hymns would differ from translating a scientific manual like the YJ, I wanted to see what changes occurred in word choice within the semantic sphere of sacred or religious literature. Would a verb used in the Sanskrit works have an equivalent in the Greek or Latin that was derived from the same PIE verbal root? Even better if it didn’t since I’d get a sense of the semantic transformations of these all-important PIE verbal roots took on different meanings as they moved and evolved into descendant languages.

Second, and I admit that this is rather hubristic, I thought that since I’d been studying South Asian religious literature for quite a while as an undergrad and in graduate school and had been raised Hindu, that my perspective on the work would differ from those of an ancient translator. Finally, I was interested in questions of when a translator would translate a term and when they would transliterate and sought to explore the calculus of making that decision. A sticking point in the academic discourse of the exchange of scientific knowledge in antiquity, is that certain Greek astronomical and astrological terms are transliterated into Sanskrit[3], and scholars seem to disagree on exactly why a translator would choose to do that when congruous terms could have been found within the Sanskrit lexicon. The now outdated explanation is that this phenomenon demonstrates the unidirectional flow of rational “scientific” knowledge from the West to the East, but this Orientalist validation of Occidental knowledge systems fails to account for the conservatism of Brahmins towards foreign knowledge and peoples. Thus, the selective integration of foreign knowledge followed much deliberation by the scholars derived from the elite Brahmin class. One might argue that this was to facilitate easy conversations between astral science (astronomy and astrology) experts working in different parts of the world. Mathematics has always kind of served as a universal language and it seemed like astral sciences did too. If math was a sort of universal, numerical grammar that transcended a language’s geographic boundaries, then the application of these mathematical rules to practical and quotidian issues seems to be the astral sciences’ purpose. Authors in the Mediterranean, Near East, and South Asia were aware of the astral sciences’ global importance and sought out engagement and interaction with those working elsewhere. Considering the reality that all translation is an interpretive act, how then does the translator balance their hermeneutic responsibility to convey the intent of the original work to their reader in a different language with their need to stay faithful to the original source?

After completing our translations for the prose comp course, we were tasked with comparing ours to the “original” to see if we captured the author’s style and structure. This is where things got a bit interesting for me. Because of some late-night research internet rabbit-holes, I knew that there was a Sanskrit translation of the New and Old Testament completed in the early 19th century by the Biblical Society in India primarily for proselytization purposes. But what this project led me to discover now was that I was – perhaps unsurprisingly to you, my dear reader – not the first philologist to translate Sanskrit literature into Greek and Latin, the European academe’s lingua franca. The origins of this practice actually lay in the Mughal Empire which governed large swathes of modern India before losing territory to the British.

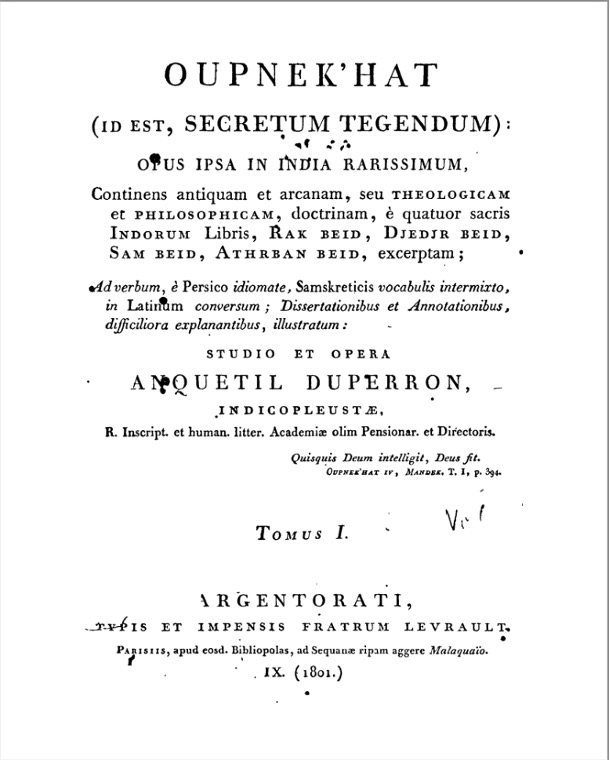

Sirr-i-Akbar, which translates from Persian as The Greatest Secret, was a translation of 50 Sanskrit Upaniṣads [4] into Persian by Mughal prince Dara Shikoh in 1657. Shikoh was the most religio-culturally progressive heir-apparent to the Emperor Shah Jahan, but was executed by his younger brother and usurper Aurangzeb before ascending the throne. This tale inspired John Dryden (yes, our very own Dryden of Virgil translation fame) to write a play about him which was apparently the “Hamilton” of its day in London.[5] Shikoh undertook this translation project with a desire to link Sufi and Hindu mysticism and worked with Brahmin pandits from Kashmir to produce a translation that made Sanskrit religious philosophy legible to Islamic scholars. It’s unclear whether it had this intended effect, since it isn’t until 1796 that Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, the first French Indologist, who was trained in Persian but could never find a willing Sanskrit teacher during his travels throughout India, translated and published the Persian work in a 900-page two-volume set titled “Oupnek’hat (id est, secretum tegendum).”

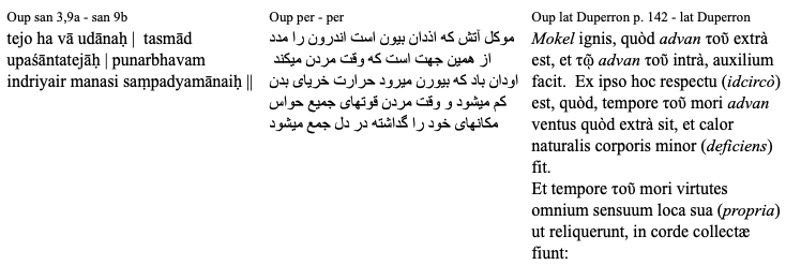

In 1801, he published his translation of this Persian version into Latin, but his French translation was published posthumously. This really was the first translation of a Sanskrit work into Latin for the broader European intelligentsia, though the fact that it was itself produced from another translation presents the reader with various challenges. Duperron reveals his translation process: word for word (ad verbum) from the Persian language, mixed with Sanskrit terminologies (Samskreticis vocabulis intermixto). The reader must know Latin, but also some Persian and Sanskrit from which words are mixed into the Latin translation. Occasionally, there’s even a Greek article thrown in as you can see below[6]:

In some ways, it was truly a scholar’s translation, but the fact that it was not produced from the original Sanskrit and the printed edition did not include the Sanskrit original creates some major misconceptions of the text as it reaches its European audience. First is the notion that the information in the Upaniṣadic corpus was somehow a great secret. The Sanskrit word Upaniṣad has multiple definitions and can be interpreted as meaning the knowledge that passed from teacher to student sitting near one another. But some of the early Upaniṣads themselves claim to be expounding secretive and mystical doctrines to their readers, so while Shikoh was not wrong, one might say that Shikoh’s translation of the title only served to further enhance the Eastern text’s novelty and mystical appeal to European audiences.[7] With Duperron’s translation of the Persian as secretum tegendum, the Sanskrit’s multiple meanings fall away and readers are left with the single interpretation of this word through the Persian title Sirr-i Akbar. Second, the grouping of the individual Upaniṣadic texts varied regionally in South Asia, but Shikoh’s collection of 50 Upaniṣads as a single volume created a new grouping meant to parallel the monobiblic Abrahamic traditions, which itself shaped the way European readers engaged with Sanskrit literature early on. In reality, there were more than a hundred treatises that fell into the category of Upaniṣad, so readers had to be made aware that this was a curated selection that likely helped Shikoh make the case that his edition of the Upaniṣads was the kitāb-al maknun (Hidden Book) referenced in the Qur’an 56:78. As a translator Duperron was true to his source text’s intentionality.

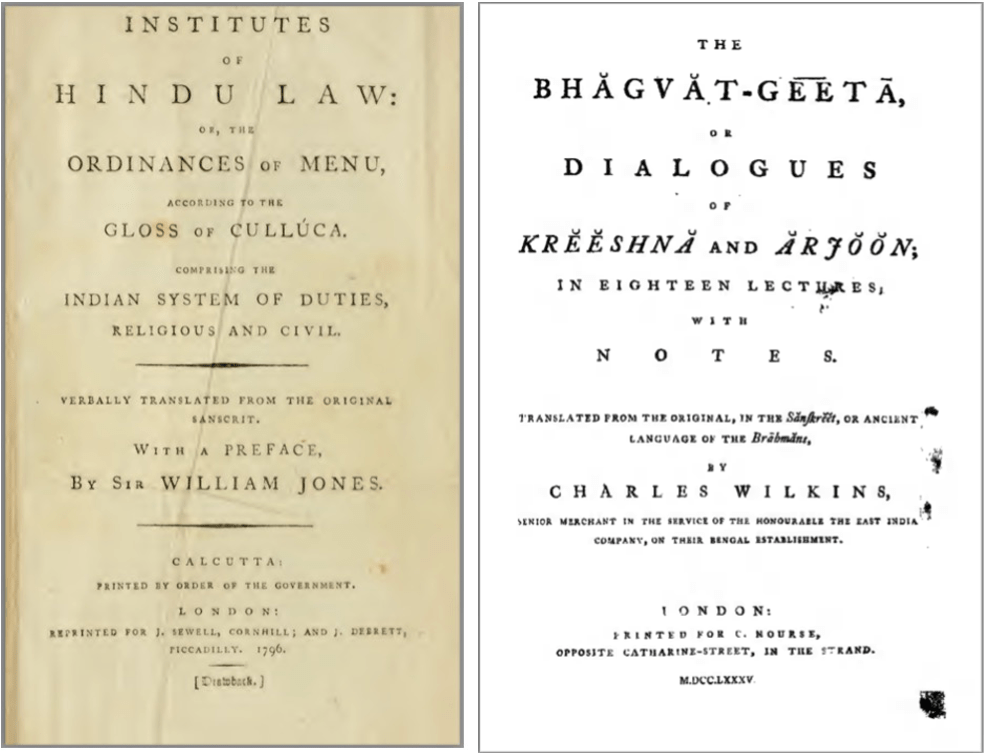

But before Duperron, the British had prioritized studying and producing translations of Sanskrit works after setting up the East India Company’s HQ in Calcutta. The first translation of a work from Sanskrit to English that made a mark on European audiences was the English translation of the Bhagavad Gīta from the original Sanskrit by Charles Wilkins in 1785. This followed Sir William Jones’ 1776 publication of his translation of the Manusmṛti Dharmic law codes to create a colonial Hindu law code mirroring English Civil Law. After facing similar difficulties to Duperron with pandits being unwilling to teach him, Jones finally found a doctor willing to teach him Sanskrit. Having trained under Jones, Wilkins translated this specific portion of the Sanskrit Epic poem Mahabhārata (MBh.) because it contained a discourse by the Hindu god Kṛṣṇa on how humans could attain spiritual liberation through proper actions and devotion to him alone. The text’s emphasis on Kṛṣṇa as the singular supreme deity was problematically interpreted as a sign of Hinduism’s “development” from old-world, uncivilized polytheism to a more acceptable monotheism that reflected Abrahamic religions. This served the East India Company’s goal of convincing shareholders that understanding Indian culture through translation projects and Sanskrit education was worth their investment.

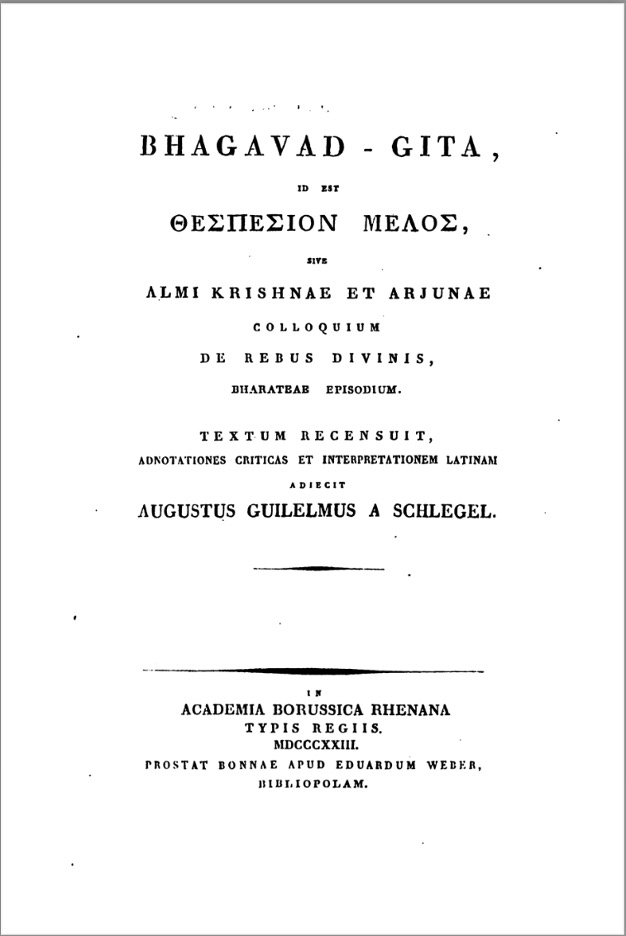

So, given that translations of Sanskrit works already existed in English, a colloquial language which would have been more legible to Europeans than the Sanskrit original, why bother producing Latin translations of Sanskrit works? Well, for the German Indologist August Schlegel (1767-1845), who composed an 1823 translation of the Gīta into Latin accompanied by a critical edition of the Sanskrit and commentary, it wasn’t merely to open up Sanskrit literature to non-Anglophone Europe, but to use a language most analogous in its grammar and structure to Sanskrit itself that would be legible to European audiences.

Schlegel explains that Latin – as opposed to English or French – is highly suitable for translating Sanskrit books because of its syntactical concision, which Greek lacks, and because Latin isn’t “burdened with the baggage of particles, articles, and pronouns.”[8] It appears he’d read Duperron’s translation and taken issue with its polyglossia. But his note on the merits of Latin seems somewhat self-contradictory:

“However, the Latin language is highly suitable for translating Sanskrit books. It is not burdened with the baggage of particles, articles, both definite and indefinite, personal pronouns, and auxiliary verbs of various genders, which many of the languages of modern Europe are compelled to carry along with them, due to the poverty of endings by which the genders, numbers, cases of nouns, persons, tenses, and moods of verbs are aptly and with a certain melodious sweetness distinguished…This latter province is proper to those words which are commonly called abstract. Both Sanskrit and Greek abound in such words; unlike most languages, Sanskrit generously admits abstract words even in poetry. It cannot be denied that in this genre too, the Latin language is too narrowly circumscribed: Romans, more concerned with practical matters than with the subtleties of idle wit, did not bring forth anything in conversation that would be repugnant to popular use.”

Do the benefits of Latin’s concision then really outdo Greek’s clarity for transmitting philosophical abstractions (pace Cicero Fin. 2)? Below is an example of the Devanāgarī with transliterated Sanskrit, followed by Schlegel’s Latin, and my Sanskrit-English translation of BG 11.5 where the god Kṛṣṇa reveals his viśvarūpa, or supreme form, to Arjuna, the primary protagonist of the epic:

श्रीभगवानुवाच

पश्य मे पार्थ रूपाणि शतशोऽथ सहस्रश: ।

नानाविधानि दिव्यानि नानावर्णाकृतीनि च ॥ ५ ॥

Śrī Bhagavān uvāca

paśya me pārtha rūpāṇi Śataśo’tha sahasraśaḥ |

nānāvidhāni divyāni nānāvarṇākṛtīni ca ||

Almum Numen loquitur:

Ecce, Prithae fili, formas meas centies, imo millies multiplicatas,

varias, aetherias, diversas colore ac specie.

Divine Kṛṣṇa said:

Behold, Partha (Arjuna), my hundreds and thousands of forms,

their appearances varying in divinity, colors, and shape.

Here, Śri Bhagavān, an epithet for the Hindu god Kṛṣṇa, becomes Almum Numen. Strictly speaking, śri is an honorific, merely meaning “radiant” or “resplendent.” Schlegel’s choice of Almum suggests the idea of “nourishing” or “propitious,” epithets reserved for fertility deities, like Venus[9] and Ceres, or the Earth[10] herself. Perhaps he had in mind the goddess Śri, also known as Lakṣmī, who is the goddess of fertility, wealth, and royal power. Bhagavān means “venerable” or “divine and illustrious one.” In Sanskritic works, bhagavān is often an agentive deity (Kṛṣṇa in this case), but in the Roman context, numina often manifest through an omen interpreted by divination. Though it can appear in a more concrete form, it is often used in describing divine power present in a particular place[11]or the statues of divinity in a temple.[12] As a reader of his translation, I wonder how he imagined Kṛṣṇa in his mind’s eye. One wonders why he didn’t just use beatus deus or even a more literal translation from the Kṛṣṇa’s name as the “Dark-Skinned One” as he is often painted using deep blue-black pigments or carved in black stone. If Schlegel were trying to give his readers a more accurate literary image of the Hindu god, he could have termed him the Deus Caeruleus, but perhaps the “Dark Blue God” would offend Christian sensibilities while simultaneously invoking the pagan deity Poseidon in the minds of these Classically trained readers? Either would have detracted from the favorable way in which he sought to depict Hindu religion to his European readers.

While he doesn’t explicitly answer our question, two possibilities come to my mind. First is that in this early phase of Indology, scholars were just as interested in linguistic exactitude as they were in fostering the notion that India was, perhaps, the ancient Germanic and Indo-European prehistoric homeland. To them, India served the role of an antiquated but noble ancestral culture due in no small part to the erroneous early philological theory at the time that Sanskrit was the oldest of the Indo-European languages from which Germanic, Greek, and Latin descended. Schlegel is likely following suit with Charles Wilkins’ interpretation of the Gīta’s Kṛṣṇa-centric theology as signaling Hinduism’s turn towards monotheism.

Second – and this point builds off the notion of India’s antiquity – is that using a term like numen in place of deus presents the reader with a more abstract form of Kṛṣṇa, one that is not necessarily anthropomorphic. As a reader of the 8th century BCE Upaniṣads, Schlegel likely had in mind the more abstract form of the singular īśvara present throughout those texts. The use of numen aligns this Indic notion of divinity more closely with the ancient Roman conception of divine will, shown through a divine nod of assent, thereby chronologically placing Brahmanical religion alongside ancient Mediterranean religions. This marks them both as relics of a distant past, but while ancient Greece and Rome “developed” into the 19th-century cultures of Europe, India remained as it always had. With this admiration of its antiquity eventually arose cultural tensions and nationalist fears over the possibility of 19th-century Europeans originating, not from the Mediterranean cultures they admired and fetishized, but all the way over from South Asia; Darwin’s and Wallace’s theories on evolution coming into vogue in the latter half of the 19th century only heightened these emotions.

Schlegel’s Latin vocabulary choices and reticence to use transliterations of the Sanskrit, lead him to problems of his own. In the process of translating into another ancient language, Schlegel subsequently ends up having to borrow approximates for Sanskrit philosophical and theological concepts from pre-Christian Rome. So, while he sought to produce a more exacting translation of the Sanskrit original by employing Latin, we find that he runs into the problem of invoking ancient Roman cultural references in the Indian context. Now, considering that August Schlegel and his brother Friedrich founded Jena Romanticism, it wouldn’t seem out of the question for him to purposefully archaize Indic culture to make it appear more arcane, esoteric, and obscure, as something wholly unfamiliar to his readers to heighten emotions and emphasize the material’s sublime qualities.

I find it rather funny that it also placed ancient Indian poets in the company of Milton, Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, Linnaeus, and other European neo-Latin writers, all using this ancient sacred language to explore and understand Nature from a scientific perspective. Yet, there’s little question that his attempt to translate directly from Sanskrit into Latin produced a much more comprehensible text for the well-educated reader, one that could be read without prior knowledge of Persian, Greek, Latin, and French transliterations of Persian pronunciations of Sanskrit. But how would a European reader who’d never been to India or seen depictions of Kṛṣṇa visualize this almum numen? Here is where the translator, no matter how skilled in the languages in which they’re writing, hits an obstacle: almum numen doesn’t really present an image of Kṛṣṇa in his viśvarūpa, the subject of this crucial section of the Gīta. This was his gigantic, supreme, all-encompassing form with hundreds of heads and arms, breathing fire with some and consuming all created matter with others that was visible only to Arjuna on the Kurukṣetra battlefield.

Most translation theorists have discussed Post-Classical Latin’s suitability as a European lingua franca because it was Eine Sprache ohne Sprachgemeinschaft a “language without a language-community” by the 9th century CE. This meant that there were enough people who could read it across Europe which made it possible to discuss ideas across politico-linguistic boundaries. Like Sanskrit, Latin ensured that the readers would always be of a particular social class and the language itself straddled the sacred and secular worlds. This attempt to translate the South Asian Lingua Franca into the European one mirrored Europe’s 18th-century rediscovery of ancient Greece and Rome through archaeology and classical studies. Now through colonial conquest, they were “discovering” India’s past, its peoples, and its literatures, and placing them in conversation with one another – directly and indirectly drawing connections in the minds of their readers between the still extant literatures and religious practices of India, and those of the pre-Christian, ancient, Pagan Roman empire. A part of the past was still alive all the way over there in India, in a space and among a people markedly non-European. What made Indic philosophical and religious material so fascinating was exactly what posed a danger to academicians of a Eurocentric bent.

So, while I don’t remember what grade I received on those prose comp projects, I think back to that project often in my more recent work on the ways in which Classical Studies and Sanskrit originated from comparative philology and constantly shaped one another throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Each discipline seems to have defined itself against the other, a multi-century conversation I plan to tease out in my second book project. As I now translate from Greek, Latin, or Sanskrit for my own teaching and research, I think about my prose comp experience: who was I translating for?

Engaging in this particular translation project highlighted the ways in which translation really is similar to ekphrasis. It asks the translator to convey, in his neo-Latin translation, Kṛṣṇa’s divine form and Arjuna’s reaction to it. In his Contra-Instrumentalism Larry Venuti discusses the problems with “instrumental” translation which he says “conceives of translation as a reproduction of an invariant form, meaning, or effect” in another language.[13] Instead of this, Venuti argues, translation should be considered a “hermeneutic” in which the produced text inherently varies from the source texts in form, meaning, and effect in accordance with the interests of the receiving culture; every translator must keep in mind their audience’s existing knowledge of the source text’s culture before writing a translation which renders the source culture legible. This becomes particularly relevant when translating sacred literature since every word of the original text bears a particular set of meanings to a reader trained in its original context which a translation can never truly capture in a way that would satisfy the one who knows the original text. But if the translation creates the same sense of wonder in the reader as the original, then we might say that it succeeded to a certain degree, granted we concede that in the case of Schlegel’s Gita, none of his readers would sing or chant his translation in an āśrama or temple. But this isn’t the intent of Schlegel’s hermeneutic approach to translation, as we discussed earlier.

But the question of translation gets further complicated with a text like the Gīta, in which even the reader of the original Sanskrit is reading a second-hand account of the interaction between Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna. Dhṛtarāṣṭra, the blind king of Hastināpura, hears a narration of the war’s events from his servant and charioteer Sañjaya who, attending the king in his palace, is granted divine sight solely for this purpose. By the time the 19th-century reader of the original Sanskrit is engaging with the text, it’s already gone through multiple interlocutors. Tradition dictates that Sañjaya’s narration of the Gīta and the entire Mahabhārata epic poem was uttered by the Sage Vyāsa to Gaṇeśa, the elephant-headed god, who wrote it down on palm leaves for three uninterrupted years. As far as the surviving material record suggests, the epic was written down sometime before the 2nd century CE, when we find the earliest known chapter list for the MBh., in the Spitzer manuscript. The pandits working with Wilkins as he produced his English translation were likely using manuscripts from the 16th century, and Schlegel produced his Latin translation after reading Wilkins’ English translation and a Sanskrit manuscript of the text. Thus, by the time a 19th-century European reader engages with the Viśvarūpa passages, the description of Kṛṣṇa’s divine form has been through at least five interlocutors, a lengthy game of textual telephone which further emphasizes the inherently ekphrastic nature of translation. The only individuals to ever see the Vişvarūpa were Arjuna and Sañjaya, and we, the modern readers, are left grappling with Sañjaya’s ekphrasis of Kṛṣṇa’s terrible and awesome visage which no one has actually ever seen.

If ekphrasis is a “mirror on or in a text” as Jaś Elsner and Shadi Bartsch[14] suggest, then tracing the Gita’s transmission history through its myth-historical textual transmission from the version Gaṇeśa inscribed all the way to Schlegel’s own work presents us with something like a house of mirrors at a carnival with each presenting the reader a somewhat distorted form of the original. In each reflection, the “original” meaning of the text becomes modified by the reader’s preconceived notions of Indic culture, and as they examine the text in the metaphorical mirror, they see their own reflection along with it in another mirror. Thus, the translator’s identity, their cultural assumptions, and their intended audience are never truly absent from these reflective and distortional acts, and in each translative event, the interpretation of the translation varies in its form, meaning, and effect, much like Venuti says occurs in the Hermeneutic approach to translation. Schlegel, despite his intentions as stated in his foreword, fails to produce an “instrumentalist” translation (a la Venuti) that serves as a reproduction of an invariant form, meaning, or text; it isn’t even a Latin verse translation.

Conceptualizing the ekphrasis of Kṛṣṇa’s supreme form being reflected through this room of mirrors, we get a sense of ways in which all translations are often themselves ekphrases of the original text, distortions and all. Murray Krieger’s discussion of enargeia as the goal of ekphrasis defines it as the ability of a vivid and clear translation to place the object of description in the reader’s inner eye and evokes the intended empathetic response.[15] Acknowledging translation as ekphrasis grants both translator and their reader a bit of grace as they engage in their respective endeavors. So, in the end, it’s okay if your imagined image of Kṛṣṇa looks a little different from Vyāsa’s, Gaṇeśa’s, Wilkins’, or Schlegel’s because no photograph of Kṛṣṇa in his Viśvarūpa exist (much like Achilles’ Shield), though manuscript paintings and sculptures, like the example from the Met Museum (right), aid in our imagining the moment.

Were you left in a state of wonder of the transcendent event after reading the passage in any language? Yes? Then the text (original or translation) served its purpose. Were you kind of confused by how exactly to picture these hundreds and thousands of forms of Kṛṣṇa appearing simultaneously? I think that’s kind of the point too – it was overwhelming for Arjuna and it overwhelms us. Consider too how this literary and visual image transformed as the Mahabhārata made its way through Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia during the medieval period.

Now, I don’t think my prose comp translation of 20 verses from this section of the Gīta left my audience (i.e., my professor) in a state of amazement, but I’ve made peace with that because years later, I think I found a purpose for those assignments. For what it’s worth, here’s my Latin prose comp translation from 2018 complete with original footnotes:

Beatus Deus dixit:

Ecce schemas meorum, Partha[16], quae sunt centumgemina milligeminaque et multimoda divina[17], et innumera colore et facie[18].

Oh, and if the translation above evokes any sort of “empathetic response” deep within your mind’s eye through its enargeia, please do write me.

[1] The Classics and Colonial India (Oxford, 2013)

[2] I should note that though the late Prof. David Pingree’s initial theory of this text’s transmission from the 1970s has been critiqued by more recent scholarship, there is no textual record disproving it since our earliest surviving manuscript of the text goes back only to the 10th century CE. Furthermore, the question of how scientific knowledge circulated between ancient cultures presents numerous possibilities, among which ancient bilingualism and exchange of knowledge at large centers of learning, like Alexandria or Taxila, is, I’d argue, a strong possibility.

[3] For example, the Sanskrit Hōrā and kendra come directly from the Greek ὥρα and κέντρον, respectively and largely preserve their Greek meanings. Though, we must note that for hōrā, some suggest an etymology from ahorātra, meaning “the night and day cycle” which is equivalent to the Greek νυχθήμερος.

[4] These are a collection of Brahminical exegetical texts which discuss the nature of ātman and brahman, the individual metaphysical “self” or “soul” and the all-encompassing divine essence of the universe of which it is part. They vary in size, format, and serve as a constantly expanding corpus supplementing the fixed corpus of the four Vedas.

[5] You can find a digitized version of the 1676 publication of Aurangzebe here: https://archive.org/details/aurengzebetraged00dryd_1/page/n1/mode/2up

[6] The Matheson Trust. “Oupnek’hat.” The Matheson Trust, https://www.themathesontrust.org/library/oupnekhat

[7] For an excellent discussion, cf. Gandhi, Supriya. The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India. Harvard University Press, 2020.

[8] From Schlegel’s preface translated from the Latin by me.

[9] Hor. C. 4.15.31-32: Troiamque et Anchisen et almae / progeniem Veneris canemus.

[10] Lucr. 2.991-93: Denique caelesti sumus omnes semine oriundi; / omnibus ille idem pater est, unde alma liquentis / umoris guttas mater cum terra recepit…

[11] Tac. G. 8: plerosque numinis loco habitam

[12] Tac. Ann. 1.10: nihil deorum honoribus relictum cum se templis et effigie numinum per flamines et sacerdotes coli vellet.

[13] Venuti, Lawrence. Contra-Instrumentalism: a Translation Polemic. 2019. Nebraska Press. 1-3.

[14] Bartsch, S., & Elsner, J. (2007). Introduction: Eight Ways of Looking at an Ekphrasis. Classical Philology, 102(1), i.

[15] Ibid., iii citing Krieger 1992, 94.

[16] Decline like 1st declension noun: Partha, -ae, even though it’s a masc. name.

[17] The Skt. is divyāni, which is a pl. neut. and is a cognate with deus.

[18] Both ablatives of respect.

Leave a comment